|

|

April 01, 2013

| By Randall Fleming

|

written by Karen E. Hudson, with a foreword by Kelly Wearstler

Karen Hudson, granddaughter of one of America’s greatest architects, is the author of some rather fine titles with the purpose of unearthing the early history of Black L.A.

Unlike most coffee table books, Classic Hollywood Style offers significant text to help reinvigorate the memories of an architect whose brilliance was overshadowed by a nation’s peculiar obsession with skin color.

With the precision akin to that possessed by Williams, Hudson navigates an otherwise treacly channel that has been made intentionally murky. That Williams’ brilliant and prolific work has for so long been appreciated by so few is a loss to the melting pot culture that once defined the United States and has since come to make it an admirable nation.

With this title—and a forthcoming one that we understand will be published this year—Williams’ work can be appreciated as it was always meant.

Exterior and decorated interior shots find equal space in this impressive tome.

Few have probably been allowed to personally visit the interiors of the houses he built; this book will help satisfy that longing.

As more and more of Williams’ buildings fall victim to the Southern California concept of constant “rebirth,” documents such as this are more than art; they are historical documents.

Williams’ many subtle architectural signatures can easily hold a candle to the embellishments of architect, book designer and typographer William Morris. To be sure, Williams organic sense of design remains a pleasure to behold.

($65.00: Rizzoli Int’l Publications, October 2012, hardback 240 pages, )

|

|

|

|

March 15, 2013

| By Randall Fleming

|

Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom

written by Walter Johnson

Walter Johnson’s astounding tome River of Dark Dreams is sure to prompt heated discussions on the entire history of the U.S.

Like the Japanese novels that were popular in the 1970s and 80s (only in Japan and among bibliophiles) that imagined a post-WWII world whereby Japan won the war, River... is sure to create contention among those who dare to discuss it. Unlike those revisionist novels, however, Johnson’s endeavor is well-founded, brilliantly written and a historical reality that has been historically suppressed for too long.

A possibly defining statement may be found on page 23, early in this work, whereby the reason the Louisiana Purchase occurred may be attributed to a nearly event that remains resonant among Americans of all skin colors and shade.

“The most successful slave revolt in the history of the world and the most democratic of the Atlantic world’s anti- colonial uprisings, the Haitian Revolution drastically diminished the value of the Mississippi Valley to Napoleon.”

It was this remarkable revolt that may have dissuaded France and Spain from joining forces to prevent the newly minted Americans from establishing a significant presence on the delta, along the river and west thereof. Both world powers were well aware of using slave forces to create havoc behind enemy lines, but after the revolt even they realized that the distance and unleashed fury might be too much to handle the area.

Afterward, the empire grew via land speculation that had to be fed by an agrarian base, and that base required labor. From there the area became a voracious industry that required more slaves to produce more cotton, and more cotton to buy more slaves.

In River of Dark Dreams, we read of the vast complexities that led to war, one of the most remarkable ones being the push for world domination—or bust.

($35.00: Belknap Press /Harvard University Press, hardcover, 560 pages)

|

|

|

|

March 01, 2013

| By Randall Fleming

|

Raising Hell: A Life of Activism

written by Najee Ali

Part auto-biography, part history and part confession, Raising Hell is a book that starts out a bit slow but very quickly picks up as it traces the dynamic life of tried-and- true activist Najee Ali.

Starting out in Gary, IN and jumping back and forth between Los Angeles and his hometown, Ali eventually settles down and divulges a series of harrowing tales in which he has come to be involved.

From the Michael Jackson trial, to the unjustified murders of Latasha Harlins and Sherrice Iverson, to the 1992 L.A. riots and much, much more, Ali’s page-turning tales are raw and insightful. Perhaps the most significant one for residents of Inglewood is the chapter titled “Danny Bakewell Sr. & Poverty Pimping.”

Bakewell is the CEO of the possibly largest minority-owned real estate development firm on the west coast. With his questionably obtained wealth—which he continues to maintain via contracts with the Inglewood Unified School District—he is also a person whose behavior and diatribes tends to involve violence and libel.

When Bakewell attempted to sue the New Times, a circa 1990s weekly L.A. newspaper, the result was shocking.

Bakewell was quickly SLAPPed (Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation) owing to the obvious attempt to quell discussion of his poverty-pimping machine. Bakewell was immediately ordered to pay the weekly newspaper $25k for the litigation costs incurred to defend themselves against his frivolous lawsuit. (The publisher eventually accepted a settlement of $20k so as to not have to waste time pursuing payment.)

The fallout among area activists was harsh.

Ted Hayes was quoted as saying, “You gotta put out a press release and show the $20,000 check -- that should give courage to other news- papers to say what is going on, and to finally ask: For all the charity money Bakewell is getting, why is the black community just as poor?”

Having worked with Ted Hayes—and saddened by the decision he had to make regarding the Domes, which I also photographed being removed all those years ago—

I can almost hear him saying that in exactly that fashion.

Ali goes on to conclude that “Bakewell finally coughed up $20,000, but in so doing he provided a disquieting glimpse into how he runs the Crusade, a nonprofit that takes in about $2 million in donations annually and doles it out via grants that are supposed to help turn around minority communities.”

Such an act does not appear unusual for Bakewell, seeing as he is a real estate developer whose recent flip-flop regard- ing the Prop A sales tax— which was conceived and financially backed by real estate developers and will rely primarily on residents of Los Angeles. Instead of paying the New Times, the entity Bakewell targeted for alleged libel, the real estate mogul used the charity money ostensibly meant for bringing black people out of poverty.

Of course, the only per- son who appears to have risen out of poverty from that charity money is Bakewell, who has chosen to build and own massive houses in affluent enclaves known for being havens for narrow demographics.

Ali’s chapter on Bakewell’s behavior is significant, but it is one of many intriguing chapters. And Raising Hell is by no means a comprehensive history of black activism in southern California—but it is a significant volume, and one which sits high on my shelf of Los Angeles history.

($19.99: www.najeeali.com October 2012 • 204 pages ISBN 978-0-9834856-9-8)

|

|

|

|

March 01, 2013

| By Randall Fleming

|

Florence, Constantinople and the Renaissance of Geography written by Sean Roberts

If the world is any way upside down, it may be owed to one’s preconception laid down from maps–and by proxy, those who chart, print and distribute them. To know this is to understand that one’s purview is not at all personal or unique, but very carefully, er, mapped.

In the December 12, 2012 edition of the Wall Street Journal, it was recognized that “[a]mong cartographic misfirings, the disaster of Apple Maps is rather minor, and may even have resulted in some happy accidents—in the same way that Christopher Columbus discovered America when he was aim- ing for somewhere more eastern and exotic.”

And so it is that Sean Roberts’ fine title, Printing A Mediterranean World, is a book that may seem a specialist effort—but it is one that will change the way you look at your world, the world and worldly ways.

Like language, cartography is pervasive to the point of not being seen even as it is a staple on which we rely with every step, every utterance and every thought. Moreover, maps, in conjunction with the emergence of movable type and the greater printing press, was what helped certain cultures spread their influence over the raw power of others. As Roberts aptly puts it: “This seemingly extraordinary circumstance was made possible thanks to the emergence of an enterprising Renaissance print culture in a world still significantly with- out borders between East and West that modern readers have come to take for granted.”

To not have this title in one’s library is to fail to understand one’s own perspective from the ground up. In Printing... Roberts explains exactly why we should not ignore the history of maps. Replete with a wonderful number of maps and illustrations, it is a staple in understanding our world.

($49.95: Harvard University Press, 2013, hardcover, 336 pages)

|

|

|

|

March 01, 2013

| By Teka-Lark Fleming

|

The Economics of the Civil Rights Revolution in the American South written by Gavin Wright

Sadly, the economic engine of Inglewood’s city hall is poverty porn. Worse, it is by design and engineered by a few people whose intent is to profit from it even as they purport to be working for the very people they exploit, people who by a grander design were historically exploited overtly for centuries and in the last several decades remain exploited in a far subtler fashion.

What does all this have to do with Sharing the Prize?

Quite a bit.

Wright reaches back to the formative years of the Civil Rights movement so deeply as to purposely usurp the very term “Civil Rights”— and for good reason.

Such a premise is sure to frighten many people— chief among them the purveyors of poverty who profit from pretending to grant “power to the people”—in South L.A.

Why undo a term such as “Civil Rights”? is not the

question, however, but why did the economic aspect of genuine economy in the U.S. seem to get ignored from

the beginning? Before it was known as the Civil Rights movement, the push was for economic equality, a push that extended to education and which remains a problem with Inglewood Unified School District and its many financial scandals and recent developments by Inglewood pols who have chosen to replace well-paying, long-term union jobs with low- wage, part-time positions.

In Sharing the Prize, Wright dissects the many problems regarding why Civil Rights require an economic and educational base.

The phrase is one that subtly sabotages what was originally meant as a campaign to acquire jobs, education and freedom. The problem these days—and then—is that the economic and education goals set forth by the Movement and Martin Luther King, Jr., have been obscured in a fashion meant to make black people appear to be prone to poverty and crime.

The result is one that benefits those who set up non- profits ostensibly meant to help such people—especially in cities nationally known for having significant populations of black people regardless of their significant economic and educational status.

In present-day Inglewood, we are experiencing a dearth of such possibilities that have been engineered by people who have profited from understanding what Wright has written.

($35.00: Harvard University Press/ Belknap Press, hardcover, 368 pages)

|

|

|

|

|

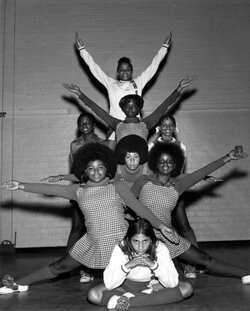

Morningside High School's "Varsity Yell" Pep Squad, 1973. Courtesy of Inglewood Public Library.

|

|

February 08, 2013

| By Teka-Lark Fleming

|

A Case Study of Inglewood, California written by Edna Bonacich & Robert F. Goodman

There is simply not enough space to fully discuss this superb book. As such, I’ll stick to basic points.

Published in 1972, Bonacich and Goodman set out to document in significant detail the manner by which school desegregation was carried out in Inglewood Unified School District. At the time, there was a distinct paradigm change occurring regarding demographics in Inglewood, and it provided a unique case study.

What the authors noted back then has become vitally important today. Some of the very people who were starting out at IUSD as well as at city hall remain entrenched there today. Moreover, the radically religious nature that has been allowed to fester at IUSD—certain school board members no longer observe the separation of church and state—means that IUSD has again become a focus of study, albeit for different reasons.

But it is not a myopic view the authors present. Most every aspect of Inglewood is preserved from the time period. It makes this title one I strongly suggest folks seek out and read.

(Praeger Publishers, 1972, 6” x 9”, 107 pp, hardcover)

|

|

|

|

February 08, 2013

| By Randall Fleming

|

Emancipation and the Act of Writing written by Christopher Hager

From the opening sentence to its final sentiment, Word by Word wastes no words stating clearly the importance of its topic: literacy and its paramount importance to knowing how to free oneself, remaining vigilant and understanding the words of those whose only intent is to op- press others that they may live off their blood, sweat and toil.

It was riveting to read, as early as the introduction, seemingly prescient revelations such as, “By writing out the clause in Article II that begins, ‘the president Shall be commander in chief of the Army and navy of the united States,” he taught himself to spell ‘president.’” It would be a shame in this day and age were a writer imagining him- or herself to possess any significance yet to misspell such a mighty word as “President.” It bespeaks the importance of establishing and maintaining one’s writing (and reading) skills in the perpetual campaign to beat back the dark- ness of ignorance, corruption and oppression.

The slave owners of the Deep South feared that black slaves learning to write would be “unsafe” and did all they could to prevent such lessons from occurring. Publicly, however, slave-owners attempted to declare that the slaves could not write owing to their innate biological inferiority.

Nevertheless, slaves did learn to write, and there are samples presented that negate both the slave-owners' and the abolitionists' perceptions.

(hardcover, $39.95: Harvard University Press )

|

|

|

|

February 04, 2013

| By Randall Fleming

|

written by Joel L Rane

illustrated by Raymond Pettibon & Cristin Sheehan Sullivan

This book resonates in many ways. I was never a librarian, but I am a Brooklynite who to this day carries his Brooklyn Library Card—and will never forget cutting his newspaperman’s teeth on mob-sponsored community newspapers that remain wellfed to this day. And I am also a fan of the Dick Riordan L.A. Library and all its vaults, nooks and crannies.

It is a bitter albeit hilarious, hateful yet hopeful, and brilliant book for its insider disclosure. Like teaching, working at a library is a career that requires complete exposure to a volatile element that is street life, gang members, rubber room rejects and all manner of danger—but pays remarkably little.

In Scream at the Librarian, we get a dictionary of mental delinquents that helps one to understand just what really happens.

It is scary, sad and bitter—but it may well be the last bit of limited art that one will be able to afford by a writer whose chapbook is illustrated by an artist whose work is found in most museums of modern art on the west coast. The faux quartercloth, letterset cover printing is a tangible aspect that makes the fingers tingle—right before the brain screams as the miscreants of the street trickle into the library on 5th Street.

(softcover, letterset press, $5: Booklyn, 37 Greenpoint Avenue, 4th Floor Brooklyn, NY 11222 www.booklyn.org)

|

|

|

|

|

Scene from Birth of a Nation

|

This coffee table tome is neither by Taschen nor is just for the table; it is meant to be examined for the cumulative testimony created during the 19th century. Taken primarily from the venerable Harper’s Weekly during the period of the American Civil War through Reconstruction, Overton reproduces images that helped shape Americans’ perceptions of ethnic groups. While many of the images by renowned illustrators such as Thomas Nast and Joel Chandler present exaggerated caricatures of black people, many of the images are more subtle and remain in use to this day. One need but read any daily edition of the Wall Street Journal to find articles that constantly link black people with only crime and poverty, or open one’s mail to find circulars that promote “the good ol’ days” by selling “free” civil war anniversary coins that celebrate the FIRST Battle of Bull Run.

No lesser authority than the Washington Post has recognized the problem, even if the vast majority of American news media has swept it back under the rug. In the 1974 book Of the press, by the press, for the press (And others, too), published by the Washington Post and Dell, Richard Harwood, in a memo dated 18 March 1971, noted that “[I]f we decide that the only ‘newsworthy’ facts about black people are facts about crime, public welfare and revolutionary rhetoric, we create a stereotype and deny the diversity of 20 million people.” It is a fact that has not been overlooked by the people who bring you Jerry Springer, MTV’s Real World and VH1’s Flavor of Love. Overton’s book is a massive endeavor that seeks to offer research into a peculiar problem by offering commentary, quotes and images from a narrow period. There are the rare instances where the burden seems to teeter (such as the spread that features a photo each of Liz Taylor and Snoop Dog; I was unable to understand the relation other than the two being popular celebrities), but that may be owed to his being intimately associated with the entertainment industry. Despite the one or two reservations,

The Media is a book that deserves its place among too few titles that have been published on the topic of news media and skin color.

www.ProStarPublications.com

or

$45.00: ProStar Publications • 8643 Hayder Place Culver City, CA 90232

|

|

|

Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid

edited by John Stauffer and Zoe Trodd

It is said that “to the victor goes the spoils,” and among such spoils is the pen with which to write history. After all, it is difficult to refute an account when one is dead. In his letters John Brown understood this intimately and foresaw a day when his campaign to be Moses in North America might fail. While the 1859 raid on Harper’s Ferry did indeed fail soon after its start, Brown’s campaign lives on. Granted, history has done as much as it can to erase the significance of the events leading up to the raid; have a gander in any pre-2000 history book published in the United States and read what little is offered.

(Read More)

|

|

|

|

December 10, 2012

| By Teka-Lark Fleming

|

The long-running, annually published title Attacks on the Press analyzes press conditions and documents new dangers in more than 100 countries worldwide. Possessing the entire library since 2001—the year that changed my life, even as others close to me lost theirs— keeps me aware of what can happen abroad, at work and certainly at home. Even for journalists who live in the free world’s urban centers, eternal vigilance against hired thugs and elected officials remains paramount.

In the Americas, national leaders are building elaborate state media operations to dominate the news and amplify their personal agendas. In European and African nations, authorities are invoking national security laws and deploying intelligence services to intimidate the press. Such measures are particularly prominent in the United States, and perhaps nowhere in the country are such measures daily attempted in Los Angeles and NYC.

To be sure, Attacks on the Press is the world’s most comprehensive guide to international press freedom.

($30 from Brookings Institute: http://www.brookings.edu)

|

|

|

|

December 10, 2012

| By Randall Fleming

|

In his first novel, The Bus, author Steve Abee is on a bus. He observes from the windows of the practically defunct MTA Line 26 life as it goes by—as he goes by it—starting near downtown along 7th Street, up Virgil until it becomes Hillhurst, then west on Franklin and eventually to other points.

In Johnny Future, Abee has returned to the point of arrival, not far from where Vermont Ave. crosses Hollywood Blvd., west of where the latter ends at the collision-inducing intersection that marks the end—or beginning—of Virgil—or Hillhurst—in the area at which the three points of East Hollywood, Silver Lake and Franklin Hills meet in the easement of what hipsters imagine is Los Feliz. Like the preceding sentence, the intersection is confusing the first few times. But Johnny Future is not confused, and Johnny Future, while a significant sleeper, is not confusing.

Like Slackers but with a backbone of a protagonist who never peels away to allow the next “protagonist” to take the figurative baton to the subsequent one, Johnny Future seems to have little talent beyond surreptitiously naming the many former and current landmarks of the area (Onyx Café, Yucca’s, Barnsdall, et al.) while seeking to score a few rails of meth, some chicken to munch, a plastic Western Exterminator statue to punch... But a plot suddenly plunges Future into action and there’s no stopping, no going back, no slowing of page-turning until the explosive end. From downtown, to El Segundo, to the harrowing showdown between the LAPD and Future as he carries his dying grandmother—who he valiantly and violently rescued from an old folks’ home in the Valley—back to her lover and Future’s friend, the chase is non-stop once it starts.

Abee is one of the better local writers who has long been a part of Los Angeles and who knows the area better than some may want to intimately know even as they pretend to live in edgy areas.

This book is a road map to how things used to be in the emergent hipster areas, and may be pointing the way back to how it might be again.

Rare Bird Lit www.RareBirdLit.com

|

|

|

|

December 10, 2012

| By Randall Fleming

|

Having intimately known a number of instructors—teachers, professors, a principal or two—in my travels and relationships, I approached “Teacher...” with a heavy sigh of ennui.

Although I had never been a teacher, I felt I knew more than enough abut the miseries of being a teacher. I imagine that, were I put to the test, my presumptuous attitude would have received a C-, at best.

Author Scott-Coe wastes no time in taking the reader into the pit of despair, humiliation and absurdity that is a teacher’s existence—and that’s what happens before the figurative first bell rings. The politics that require subjugation, being a whipping boy for incompetent parents, serving as an excuse for shadowy administrators and ultimately being offered as a sacrifice for overpaid politicians, is all in a day’s work for the typical teacher. One wonders why anyone would go into teaching.

Nevertheless, and perhaps in spite of it, the utter horror of a teacher’s milieu is well conveyed in this fine title. The book is a page-turner, even in this world of reality shows, YouTube atrocities and bizarre on-line pornography. Were it adapted properly, this book would make a great film.

The stoic subtitle suggests that there is much to endure and little to gain from the world of teaching, but Scott-Coe proves otherwise—if at least that she brought to the fore a fantastic book that is a fascinating read even as it divulges the dreadful occupation. Drawing on well- penned pieces about the parallels between teaching and motherhood, whereby the virgin-whore complex is invoked by way of the teaching profession inviting “sentimentality on on hand and harsh judgements on the other, Scott-Coe deftly exhibits many anecdotes whereby the public measures a teacher’s success “by degrees of sacrifice to the idol of childhood” even as the work is too often regarded by the parents as “glorified day care.”

Sinclair Lewis would be greatly appreciative that Jo Scott-Coe has picked up the torch.

($16.95 from Aunt Lute Books, P.O. Box 410687, San Francisco CA 94141 www.auntlute.com)

|

|

|

|

November 03, 2012

| By Randall Fleming

|

written by Chip Jacobs

For buffs of obscure, possibly arcane, L.A. history, The Ascension of Jerry is a title for your shelf. (Read More)

|

|

|

|

November 03, 2012

| By Teka-Lark Fleming

|

Claude C. Davis, a Tuskegee Airman whose task was to pilot a B-25 Mitchell during WWII, was part of the never-deployed 477th Bombardment Group. (Read More)

|

|

|

|